"He who is determined to write history in literary form should avoid the early history of Scotland."

A quote by the renowned historian A. O. Anderson from 1940

Still, it's

such a fascinating period, right?

The Picts

Click here for the Pictish stones index

The Picts, or - as Frederick Threlfall Wainwright famously phrased it - "The Problem of the Picts". An enigmatic people who arouse so much vivid discussion to this very day.

Pictish stones

As with everything concerning the Picts, there is a lot of debate about the Pictish stones. What were they for, what is on them, how to divide them, what are the symbols, how come some of them are still so well-preserved even though they were carved into sandstone? I wish I could say that they are now generally admired, but even that is not true. Some stones are still buried inside a building, used as lintels or slabs or whatever, their value seriously disregarded. Others are languishing outside, lone remnants of a once glorious past.

But some are truly appreciated in all their beauty.

To differentiate a wee bit between the different stones, I'll roughly divide them into three categories, but remember that this is not a finite division. It's just a simple guide.

The first class is stones with only symbols on them, like one of the stones at Abernethy. Over fifty symbols have been identified so far. Some represent beasts (e.g. fish, eagle); some are practical things (e.g. comb and mirror); others are truly symbolic (crescent and V-rod, or double disc and Z-rod). Some historians have tried to decipher them and put people's names on the symbols, which makes for a wonderful hunt through history. Find out more as you read about each different stone listed below.

The second class is stones with symbols on one side and christian figures on the other, usually at least a cross, like the Dunfallandy Stone or the Drosten Stone. Entire moral lessons can be carved on those stones.

The third class is stones without symbols, like the St Andrew Sarcophagus or the Dupplin Cross.

Just for the fun of it, I will give the names W.A. Cummins thinks some of the symbols stand for.

Index

Aberlemno Stones // Burghead Bull(s) // Dandaleith Stone // Dunfallandy Stone // Dupplin Cross // Eagle Stone // Eassie Cross slab // Edinburgh National Museum of Scotland // Elgin Cathedral // Fowlis Wester Stones // Groam House Museum // Hilton of Cadboll // Logierait Churchyard Cross slab // Meffin Institute - Forfar // Meigle Museum // Nigg Stone // Portmahomack // Rosemarkie // St Andrews Sarcophagus // St Orland's Stone // St Vigeans Museum including the Drosten Stone // Shandwick Stone // Struan Church Pictish stone // Sueno's Stone // Tarbat Discovery Centre - Portmahomack

Aberlemno Stones

Aberlemno is a tiny village housing not one, but four Pictish stones out in the open. Three of them can be found along the road.

Aberlemno is a tiny village housing not one, but four Pictish stones out in the open. Three of them can be found along the road.  The fourth is situated in the village churchyard. They are dated (rather widely) between AD 500 and 800.

The fourth is situated in the village churchyard. They are dated (rather widely) between AD 500 and 800.

Aberlemno III is the first you see from the car park and is a tall (2.8m) stone, featuring a cross on the front, including angels and animals and knotwork.

The back - nearly always my favourite - is divided into three parts. The top shows two gigantic Pictish symbols, the middle bit contains a hunting scene, including horn blowers, and, at the bottom, the biblical King David is fighting the lion.

The back - nearly always my favourite - is divided into three parts. The top shows two gigantic Pictish symbols, the middle bit contains a hunting scene, including horn blowers, and, at the bottom, the biblical King David is fighting the lion.

The two symbols take up a lot of space and are very clear: a crescent and V-rod above a double disc and Z-rod.

According to Cummins, this Pictish stone is dedicated to: Bridei/Brude, son of Drust.

Only a few metres further along the road, is Aberlemno V, which is significantly smaller. Whatever symbols were on it, they have all eroded, with only a curving symbol barely visible. Some websites even think this is a fake.

Only a few metres further along the road, is Aberlemno V, which is significantly smaller. Whatever symbols were on it, they have all eroded, with only a curving symbol barely visible. Some websites even think this is a fake.

Aberlemno I is the third stone and is a pure Class I Pictish stone with symbols only. It is sometimes dubbed the "Serpent Stone" because of the serpent as the top symbol. Underneath you can see the double disc and Z-rod. The bottom shows a mirror and comb. Cummins did not attach a name to the serpent symbol, but the double disc and Z-rod - as above - could stand for Drust. Comb and mirror would mean RIP.

Aberlemno I is the third stone and is a pure Class I Pictish stone with symbols only. It is sometimes dubbed the "Serpent Stone" because of the serpent as the top symbol. Underneath you can see the double disc and Z-rod. The bottom shows a mirror and comb. Cummins did not attach a name to the serpent symbol, but the double disc and Z-rod - as above - could stand for Drust. Comb and mirror would mean RIP.

So here you have: in memory of "Serpent", son of Drust.

The churchyard contains Aberlemno II, a beautiful Class II stone. It is nearly two metres. The hole was not made by Pictish carvers, but was added some time in its long history.

The churchyard contains Aberlemno II, a beautiful Class II stone. It is nearly two metres. The hole was not made by Pictish carvers, but was added some time in its long history.

The front is a majestically carved cross with interlaced carving and fish-tailed horses.

The back triggers one of the most hotly debated fighting scenes in Pictish history.

The symbols on the stone are a notched rectangle with Z-rod next to a triple disc.

Underneath is a myriad of horsemen and soldiers, all fighting one another.

|

|

|

Until recently, most historians thought this depicted the Battle of Nechtansmere (or also previously called the Battle of Dunnichen). But there are some "tiny" issues with this. This Pictish stone is thought to date from the second half of the eighth century, while the battle was fought AD 685. So that's quite some time later. Secondly, the location of Dunnichen (south of Aberlemno) as battle scene has been challenged. The battle might have been fought considerably more northwards (at another place with the link Dun Nechtan). So what battle was depicted here, if not the famous battle when Bridei, son of Beli, defeated the English? An alternative might be that it was a battle fought by Oengus, son of Wrguist/Fergus, who was a rather active "warrior" king of Pictavia in the first quarter of the eighth century.

Whatever battle it is, it is a very fine stone and definitely worth the visit. Don't forget that the four stones are boxed up during the winter. So visit between April and September only. Unless you want to photograph boxes.

Burghead Bull(s)

The Burghead bulls originate from - as you may guess - Burghead which is thought to have harboured some thirty of these stones.They are really typical for this area.

The Burghead bulls originate from - as you may guess - Burghead which is thought to have harboured some thirty of these stones.They are really typical for this area.

Now you would imagine that the small museum in Burghead is where this fine specimen is from, but alas.  The few that are there are allput in badly-lit glass cages, making it impossible to take a single decent picture.

The few that are there are allput in badly-lit glass cages, making it impossible to take a single decent picture.  Which is a damned pity. But the Burghead Bulls seem to have travelled some distance by now.

Which is a damned pity. But the Burghead Bulls seem to have travelled some distance by now.

So, the picture on the top left is from Elgin Museum. The one on the right is from Inverness Museum. Finally to the left again is a Burghead Bull you can discover in the badly structured mess of the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh (try the theme "animals).

Dandaleith Stone

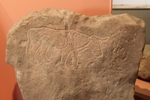

This pink granite stone is about 1.7m and was discovered during ploughing in Craigellachie in 2013. It was then moved to Elgin Museum where it takes pride of place.

This pink granite stone is about 1.7m and was discovered during ploughing in Craigellachie in 2013. It was then moved to Elgin Museum where it takes pride of place.

The Dandaleith Stone is "unusual" for a Class I stone because both sides contain symbols - and only symbols.  As they are different in style, it is assumed that the sides were not done at the same time.

As they are different in style, it is assumed that the sides were not done at the same time.

On the picture

to the left you can still discern an eagle on top of a crescent and V-rod.

The other side displays a mirror above a notched rectangle and Z-rod.

So one side may be dedicated to Dunodnat, son of Brude. While the mirror (RIP) may remember

Oengus.

Dunfallandy Stone

This was my very first Pictish stone. It is situated to the south of Pitlochry, and it is protected by glass, which makes for lousy pictures, especially with the green foliage behind it. I was fortunate enough to have the glass opened by a manager of Historic Environment Scotland. The reflection of the greenish glass still delivered horrible pictures of the back side of the stone, but the symbol side was wonderfully displayed without the glass.

This

This  beauty dates from the eighth or ninth century (not even that is a certainty). It is "unusual" in that it has five symbols on the stone:

beauty dates from the eighth or ninth century (not even that is a certainty). It is "unusual" in that it has five symbols on the stone:

the Pictish beast/elephant/dolphin - let's call it a beast - see picture on the left;

double disc (top right);

crescent and V-rod (top left and bottom right);

hammer, anvil and pincers (seen as one, see below).

As far as its meaning goes, there is this possibility: a commemoration to Edern (figure on the top left) and the female variant of Kenneth, daughter of Brude, who are the parents of the equestrian figure, Brude, son of Edern.

The hammer, anvil and pincer represent the name of the manufacturer.

Fun, right.

The figures and symbols are set within two long snakes on each side of the panel.

The other side features a cross - making it Class 2 indeed - with each arm containing spiral bosses (that's the big dots sticking out), and the interlace pattern.

The other side features a cross - making it Class 2 indeed - with each arm containing spiral bosses (that's the big dots sticking out), and the interlace pattern.

The cross is surrounded by plenty of figures of animals and angels. In reality, they are less green, but you get the picture, I hope.

|

|

|

Is it worth seeing? Definitely!

It's a real pity it is behind glass, but apparently it is not just the weather harming the stone. Some idiots (sorry, it's plain stupid to think it won't damage the stone) think it's fun stone rubbing an ancient piece of history. Now they spoiled it for the rest of us. But don't let this stop you admiring this amazing Pictish beauty.

Dupplin Cross

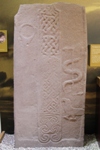

This Pictish cross is a gem, a beauty, an absolute must-see. While crosses are more plentiful in the west of Scotland, this is the only surviving complete cross in Pictland. It is nearly 3 metre high.

This Pictish cross is a gem, a beauty, an absolute must-see. While crosses are more plentiful in the west of Scotland, this is the only surviving complete cross in Pictland. It is nearly 3 metre high.

It once stood at Forteviot, where it was one of  probably four boundary markers overlooking the royal palace (sadly lost). For conservation reasons it was moved to St Serf's Church at Dunning a few miles to the south west in 2002. There you can admire it in all its glory, and if you're lucky the same enthusiastic guide will tell you all about it.

probably four boundary markers overlooking the royal palace (sadly lost). For conservation reasons it was moved to St Serf's Church at Dunning a few miles to the south west in 2002. There you can admire it in all its glory, and if you're lucky the same enthusiastic guide will tell you all about it.

If the uniqueness of the Dupplin Cross isn't impressive enough, how about this? On the picture to the right above, you can see a seemingly "blank" panel. This panel was investigated with special tools, which revealed that this particular Pictish treasure was dedicated to Constantín son of Wrguist

If the uniqueness of the Dupplin Cross isn't impressive enough, how about this? On the picture to the right above, you can see a seemingly "blank" panel. This panel was investigated with special tools, which revealed that this particular Pictish treasure was dedicated to Constantín son of Wrguist  (aka Constantine son of Fergus). He ruled both north and east Pictavia between 789 and 820 and was - as one historian describes him - "the strongest and most secure king in northern Britain" in his days. So he wasn't just anybody. The cross itself is expected to date from around 800.

(aka Constantine son of Fergus). He ruled both north and east Pictavia between 789 and 820 and was - as one historian describes him - "the strongest and most secure king in northern Britain" in his days. So he wasn't just anybody. The cross itself is expected to date from around 800.

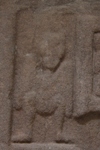

As you can see from the several pictures, the cross is beautifully decorated. The most striking feature is the figure of the horseman with very impressive moustache. This is assumed to be Constantín himself. Below the horseman, there are four warriors with shields and spears, like you can also see on the right. To the left you can see an individual playing the harp, which might be the biblical king David. Finally, there are the typical beasts and knot-work. Each one carved so delicately, it makes one wonder how the sculptures on this red stone survived until 1999 outside in Scottish weather.

As you can see from the several pictures, the cross is beautifully decorated. The most striking feature is the figure of the horseman with very impressive moustache. This is assumed to be Constantín himself. Below the horseman, there are four warriors with shields and spears, like you can also see on the right. To the left you can see an individual playing the harp, which might be the biblical king David. Finally, there are the typical beasts and knot-work. Each one carved so delicately, it makes one wonder how the sculptures on this red stone survived until 1999 outside in Scottish weather.

Like I said, this is a must-see.

Eagle Stone - Clach an Tiompain

The Eagle Stone or Clach an Tiompain (sounding stone) is a relatively small Pictish stone with two symbols on the front: a horseshoe (some call it an arch) above an eagle (hence the name). Both symbols are not the most frequent ones (Cummins estimates the former at 4.5% and the latter at 3.4% of all symbols on all Pictish stones).

The Eagle Stone or Clach an Tiompain (sounding stone) is a relatively small Pictish stone with two symbols on the front: a horseshoe (some call it an arch) above an eagle (hence the name). Both symbols are not the most frequent ones (Cummins estimates the former at 4.5% and the latter at 3.4% of all symbols on all Pictish stones).

While we're with Cummins, this stone could be dedicated to a son of Dunodnat (no name for the horseshoe/arch).

The stone is located in Strathpeffer and there is a good path leading to it. Apparently it used to be located further down the glen before it was moved in 1411.

While you're there, take a look towards the east and gaze at this fine hill... and realise it's not just a hill. It's an actual hill fort: Knock Farril. So while you're in the area: go and check it out. Why waste a good opportunity?

While you're there, take a look towards the east and gaze at this fine hill... and realise it's not just a hill. It's an actual hill fort: Knock Farril. So while you're in the area: go and check it out. Why waste a good opportunity?

Eassie Cross slab

As you can see from the picture to the left, the Eassie Cross slab is put behind glass. Never ideal for taking decent pictures.

As you can see from the picture to the left, the Eassie Cross slab is put behind glass. Never ideal for taking decent pictures.

The reverse of this Pictish stone is even more challenging to photograph. There is a "door" with metal bars to the side of it. As the bars were too tight to put my camera through (with a camera phone, that will not be an issue), this keen photographer

hoisted the camera over the top, lowered it again and tried to take pictures like that. All in all, I had some decent result.

This particular stone dates from the eighth century. The front displays the traditional, beautifully carved cross with angels in the top corners, deer in the lower right corner and this funny looking figure marching with a speer in the lower left corner.

This particular stone dates from the eighth century. The front displays the traditional, beautifully carved cross with angels in the top corners, deer in the lower right corner and this funny looking figure marching with a speer in the lower left corner.

The reverse is yet again a feast to the eyes. The Eassie stone features cows, and one of them has something around its neck (the board says it's a cow bell, an eighth-century cowbell!).

Above the farm animals are three men, a weird-looking figure in the top right corner, next to what appears to be a "tree" and then the Pictish symbols: the Pictish beast above the double disc and Z-rod. According to Cummins, we have here: Edern, son of Drust.

Above the farm animals are three men, a weird-looking figure in the top right corner, next to what appears to be a "tree" and then the Pictish symbols: the Pictish beast above the double disc and Z-rod. According to Cummins, we have here: Edern, son of Drust.

By the way, have I told you already that I really love the Pictish beast?

Edinburgh National Museum of Scotland

I will try to keep it civilised, but to put it politely, the organisation of the history section in the National Museum of Scotland is a shambles and that is putting it rather mildly. Firstly, you have to ask where the floor is because it's hidden. Couldn't find it the first time, failed to find it ourselves the second time. It's in the flipping basement.

I will try to keep it civilised, but to put it politely, the organisation of the history section in the National Museum of Scotland is a shambles and that is putting it rather mildly. Firstly, you have to ask where the floor is because it's hidden. Couldn't find it the first time, failed to find it ourselves the second time. It's in the flipping basement.

Secondly, the Pictish stones are scattered around, mixed with stones from another period, another part of Scotland or some other issue. The information boards are... Well, I would laugh if it weren't so sad.

To start, what do you make of this? Most people just pass it without noticing it at all. I did the first time I visited the National Museum of Scotland (in search of the Lewis Chessmen - another treasure hidden among other treasures). I certainly did not miss this fine piece of Pictish art when it was still in the previous museum. This is the Forteviot Arch and is a hugely significant piece of what was once a royal centre. It covers the front of a book on Forteviot: see Aitchison in my literature. But the NMS places this arch above a gigantic entrance, so nobody notices it. It was only as I was trying to get a decent picture of it, that people started looking up.

To start, what do you make of this? Most people just pass it without noticing it at all. I did the first time I visited the National Museum of Scotland (in search of the Lewis Chessmen - another treasure hidden among other treasures). I certainly did not miss this fine piece of Pictish art when it was still in the previous museum. This is the Forteviot Arch and is a hugely significant piece of what was once a royal centre. It covers the front of a book on Forteviot: see Aitchison in my literature. But the NMS places this arch above a gigantic entrance, so nobody notices it. It was only as I was trying to get a decent picture of it, that people started looking up.

Incidentally, in the same hall where the arch hangs, you can find a quote dating from the Wars of Independence (how many hundred years is that off?). Just to give you an idea of what you can expect.

Or take this magnificent Pictish stone: the Hilton of Cadboll.

Or take this magnificent Pictish stone: the Hilton of Cadboll.  "Pride of place" equals the basement in the NMS, situated next to a modern sculpture.

"Pride of place" equals the basement in the NMS, situated next to a modern sculpture.

The original reverse has been removed by a 17th-century mason who would have found a job in the NMS

for sure.

For a magnificent replica placed where the Hilton of Cadboll was originally found, please scroll further down or click here.

The remainder is organised according to theme, intermingled with various non-Pictish carved stones. The stone on the left is catalogued under "Fat of the Land - Drunk in charge - Carved stone showing drunk warrior on horse, Bullion".

The remainder is organised according to theme, intermingled with various non-Pictish carved stones. The stone on the left is catalogued under "Fat of the Land - Drunk in charge - Carved stone showing drunk warrior on horse, Bullion".

Another theme is religion, under which the stone to the right is found: "Gods of the frontier, God of the Book - The new religion and the old beliefs", found in Murthly. It doesn't even mention it's Pictish.

Same theme, subheading "Big Crosses", found in Woodray. It does mention that it contains Pictish symbols, but then again, apparently "history remains silent on these".

Same theme, subheading "Big Crosses", found in Woodray. It does mention that it contains Pictish symbols, but then again, apparently "history remains silent on these".

Now that's an easy way out.

There's more.

There's a theme on "deer hunt" and one on "Fruits of the Wild - Wild Creatures".

There's a theme on "deer hunt" and one on "Fruits of the Wild - Wild Creatures".

At long last there is one theme with exclusively Pictish stones: notably the one with "Glimpses of the sacred - Pictish Symbols". Hurray.

The stones come from all over Pictland and show various symbols: crescent and V-rod, double disc (with Z-rod), fish, notched mirror case, Pictish beast, or in the case of the stone to the right: a goose above a salmon. The reverse of this Pictish stone is the middle picture on the second row below.

|

|

|

|

|

|

And what do you make of these fine Burghead Bulls?

And what do you make of these fine Burghead Bulls?

So, National Museum of Scotland? Definitely worth the visit. But one needs patience... and calm... which I - I'm sorry - seriously lack.

Elgin Cathedral

This fine Pictish stone is found among the ruins of Elgin Cathedral, so, aye, you need to pay to see this one. But the Cathedral is more than worth is, so don't let this stop you.

This fine Pictish stone is found among the ruins of Elgin Cathedral, so, aye, you need to pay to see this one. But the Cathedral is more than worth is, so don't let this stop you.

One side of this Class 2 type is the Christian cross with two evangelists on it.

One side of this Class 2 type is the Christian cross with two evangelists on it.

The other side has two symbols - double disc and Z-rod over a crescent and V-rod - above a hunting scene. What is really special is that the most prominent huntsman has a bird of prey on his arm, so this fine stone displays falconry.

Following Cummins' guide, this could be dedicated to Drust, son of Brude.

Fowlis Wester Stones

As you can see from the picture on the right, contrary to the popular title "Fowlis Wester Stone", there are in fact two stones: one very large one and one significantly smaller. The taller one of over 3 metre is the more famous one. It is also referred to as the "great cross slab" because a cross features on the front of the stone.

As you can see from the picture on the right, contrary to the popular title "Fowlis Wester Stone", there are in fact two stones: one very large one and one significantly smaller. The taller one of over 3 metre is the more famous one. It is also referred to as the "great cross slab" because a cross features on the front of the stone.

The stone originally stood near an already demolished chapel some three miles north of Fowlis Wester. It was probably moved to the "market square" of Fowlis Wester some time during the nineteenth century. It was moved inside the church in 1991, with a replica now standing outside (and for some unknow reason I failed to take a picture of the replica in its small metal-gate enclosure).

Now to make two small complaints. Firstly, as you can see from the first picture, someone thought it necessary to liven up the scene by putting flowers in front of a majestic slab from the 800s. Deep sigh. But at least one can remove the flowers and take a second picture.

|

|

|

Secondly, and slightly more problematic, the stone is placed too close to the wall, so it is impossible (even with a decent camera) to take one single picture of the truly magnificent "back"-side. Hence, the three pictures. (Outside, you can take a picture of the whole, but then you have the additional metal bars with it.)

As you can see, this side of the stone is very lively. The top displays a single horseman with a hawk on his arm. (Unfortunately I'm too small to take a proper picture of that bit.) Underneath is a very large hunting dog above a pair of horsemen. The next row consists of a cavalry of men and one man with a cow (strange army).

As you can see, this side of the stone is very lively. The top displays a single horseman with a hawk on his arm. (Unfortunately I'm too small to take a proper picture of that bit.) Underneath is a very large hunting dog above a pair of horsemen. The next row consists of a cavalry of men and one man with a cow (strange army).

Then my favourite bit: the symbols. At the top there is a double-disc and Z-rod (I'm too wee to see that). The bottom row supposedly features an eagle, but I couldn't really distinguish it (might as well have been a grouse to me). But the crescent and V-rod is unmistakably there. Meet Bridei/Brude.

Behind the tall and famous stone, another stone is placed. Smaller, but with carving that is more delicate and which survived to this day, because it was buried within a wall for some 700 years. It is damaged to one side and there is reason to believe this may have happened during the making of the stone. Still, it's a fine piece. The cross is very detailed.

Behind the tall and famous stone, another stone is placed. Smaller, but with carving that is more delicate and which survived to this day, because it was buried within a wall for some 700 years. It is damaged to one side and there is reason to believe this may have happened during the making of the stone. Still, it's a fine piece. The cross is very detailed.

Both stones are definitely worth the visit.

Groam House Museum

See Rosemarkie

Hilton of Cadboll

This "monumental masterpiece" has travelled quite some distance and is still dispersed. It was erected around AD 800, but broke not long after. It broke again in 1674 and the bottom piece was left in the ground. A few years after that, "some barbarous mason" then removed one side (the cross-side) to create a grave slab. Vandals have always been around.

This "monumental masterpiece" has travelled quite some distance and is still dispersed. It was erected around AD 800, but broke not long after. It broke again in 1674 and the bottom piece was left in the ground. A few years after that, "some barbarous mason" then removed one side (the cross-side) to create a grave slab. Vandals have always been around.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century the stone was removed and eventually ended up in the National Museum of Scotland and do not get me started on its position there. Hold it, if you do want to read my grumbling, please find it in the Edinburgh list above.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century the stone was removed and eventually ended up in the National Museum of Scotland and do not get me started on its position there. Hold it, if you do want to read my grumbling, please find it in the Edinburgh list above.

The bottom bit was dug up in 2001 and moved to the nearby village of Balintore, where you can visit it, but cannot take a picture because of excessive glass cages and impossible lighting. For the love of...

In any case, because locals did want to show where the stone had been found, a very fine replica was created, close to its original location: at the site of the remains of a chapel (the bumps in the grass).

And honestly, it is worth visiting this replica, not just because of the setting, but also because you can admire it it all its glory (unlike in Edinburgh).

The replica is part of the Highland Pictish Trail, which we started in Portmahomack at the Tarbat Discovery Centre.  As mentioned below, close to the centre you can admire a statue called the Pictish Queen. That queen refers to the person pictured on the Hilton of Cadboll. Placed above the armed horsemen with their dogs is a female figure. Given that you had to be pretty special to have your own tribute, she must have been of some elevated position.

As mentioned below, close to the centre you can admire a statue called the Pictish Queen. That queen refers to the person pictured on the Hilton of Cadboll. Placed above the armed horsemen with their dogs is a female figure. Given that you had to be pretty special to have your own tribute, she must have been of some elevated position.

The symbols do not give away her name. At the top (barely visible) you can discern the double disc and Z-rod (Drust), underneath the crescent and V-rod (Brude) above two discs.

The symbols do not give away her name. At the top (barely visible) you can discern the double disc and Z-rod (Drust), underneath the crescent and V-rod (Brude) above two discs.

Worth the visit, even if it is a replica.

Logierait Churchyard Cross slab

This Pictish stone you can find in the churchyard of Logierait (hence the name). A rather important part is missing, but it is still impressive.

This Pictish stone you can find in the churchyard of Logierait (hence the name). A rather important part is missing, but it is still impressive.

One side of the stone displays a horseman (decapitated unfortunately) above a serpent-and-rod (so not a Z-rod, but an "ordinary" rod.

The other side is a knotted cross.

I bet that top half was used to construct something... yet again.

Meffin Institute - Forfar

This museum contains several collections found in the surrounding area, including from Kirriemuir, Glamis, Strathmartine and Wester Denoon.

Just one remark: I just cannot understand why you would put (some) stones or slabs behind glass inside a museum.

Just one remark: I just cannot understand why you would put (some) stones or slabs behind glass inside a museum.  It's not like people will insist on vandalising them with a guard looking at you. People want to take pictures, which is virtually impossible with artificial light and a glass box. It's ridiculous.

It's not like people will insist on vandalising them with a guard looking at you. People want to take pictures, which is virtually impossible with artificial light and a glass box. It's ridiculous.

Arguably the most renowed Pictish stone in the museum is luckily not behind glass, but a sign is placed in front of it, so it's yet again impossible to take a complete and decent picture of it.

Room for improvement.

The Dunnichen Stone was found when ploughing a field in Dunnichen and still bears the scars from the process (picture on the right). It was moved around for a while until it settled in Forfar.

The Dunnichen Stone was found when ploughing a field in Dunnichen and still bears the scars from the process (picture on the right). It was moved around for a while until it settled in Forfar.

The stone dates from the seventh century and you can clearly see its symbols: a flower above a double disc and Z-rod, and finally a mirror and comb. The flower is a rather rare symbol (not even 2 % of all surviving stones display this symbol) and Cummins does not link a name to it. The double disc and Z-rod is Drust. Mirror and comb stand for RIP/in memory of.

Dunnichen is derived from Dun Nechtan, with the latter being a Pictish name.

I am not listing all fragments found in the museum as there quite a lot. But here are some examples of Pictish stones displayed inside the building.

This is Strathmartine 3 and this is the top half of a Pictish cross-slab.

This is Strathmartine 3 and this is the top half of a Pictish cross-slab.  You can see some of the surviving interlace within the cross with next to it animals.

You can see some of the surviving interlace within the cross with next to it animals.

The back shows one of my favourite symbols: the Pictish beast.

The museum also displays the Kirriemuir collection, of which this is Kirriemuir 1.

The museum also displays the Kirriemuir collection, of which this is Kirriemuir 1. The top squares next to the cross show (what was assumed to be) two eagle-headed men. The bottom panels are filled with one churchman each, holding a book.

The top squares next to the cross show (what was assumed to be) two eagle-headed men. The bottom panels are filled with one churchman each, holding a book.

The back is split up in two parts. The top half includes two figures breaking bread - possibly Saints Paul and Anthony. The bottom half includes a mirror and comb and the figure of a woman- the Virgin Mary possibly.

Kirriemuir 2 displays a cross with angels sitting on its arms. Below is a hunter (for me it could also be a rambler with a walking pole), a deer and hunting dogs.

Kirriemuir 2 displays a cross with angels sitting on its arms. Below is a hunter (for me it could also be a rambler with a walking pole), a deer and hunting dogs.

The reverse features the double disc and Z-rod symbol above two horsemen and a hunting dog attacking a deer.

Kirriemuir 3 is also incomplete.

Kirriemuir 3 is also incomplete.

The front is a cross flanked with intertwined animals.

The back shows just one horseman (with dog in the left corner), but you can still make out the legs of the horse above, so there would have been two horsemen on this slab.

A final piece I wish to share is Kirriemuir 4, which has one surviving side only.

A final piece I wish to share is Kirriemuir 4, which has one surviving side only.

The explanatory note describes this stone as "an angel with drooping wings", but what is left of the angel's face tells me he doesn't look all that happy with the situation.

So, all this and more in Forfar Museum.

Meigle Museum

Like St Vigeans (further below) this is a must-see/must-do place if interested in Pictish stuff. The only thing is, you really have to look for it. We drove right past it with our eyes intent on finding it. Aye, it has a tiny sign on the side, but it's very easy to miss.

Like St Vigeans (further below) this is a must-see/must-do place if interested in Pictish stuff. The only thing is, you really have to look for it. We drove right past it with our eyes intent on finding it. Aye, it has a tiny sign on the side, but it's very easy to miss.

Meigle may be a tiny village today, but in the eighth century, it was something of a Pictish Christian hotspot. Several of the stones display clerics or angels.  The wealth of sculptured stones found in the area clearly suggests that Pictish noblemen considered Meigle important enough to have so many slabs and grave markers made.

The wealth of sculptured stones found in the area clearly suggests that Pictish noblemen considered Meigle important enough to have so many slabs and grave markers made.

The museum houses over 30 Pictish elements, from complete slabs and grave-covers, to fragments. That so many survive to this day is thanks to a local landlord who realised their significance and started gathering all the artefacts from the area. They are now housed in a small room. Pictish antiques at every square inch.

Some sources suggest that Meigle was part of the same royal estate under the king named on the Drosten stone (which commemorates Drust, son of Ferat). If so, Meigle 1 certainly does not remember the same individual, because whereas the Drosten stone features the double disc and Z-rod above a crescent, this 2m-high slab displays a fish above a serpent and Z-rod. Even better, there is reason to believe this stone commemorates a king Nechtan (the fish), and for that time period, that would match, Nechtan, son of Derile (the serpent and Z-rod).

Some sources suggest that Meigle was part of the same royal estate under the king named on the Drosten stone (which commemorates Drust, son of Ferat). If so, Meigle 1 certainly does not remember the same individual, because whereas the Drosten stone features the double disc and Z-rod above a crescent, this 2m-high slab displays a fish above a serpent and Z-rod. Even better, there is reason to believe this stone commemorates a king Nechtan (the fish), and for that time period, that would match, Nechtan, son of Derile (the serpent and Z-rod).

Meigle 1 is thought to be the oldest Pictish stone carved for the area.

Meigle 1 is thought to be the oldest Pictish stone carved for the area.

As you can see on the picture to the right, the reverse not only has the fish and serpent and Z-rod symbols, but also a mirror and comb. It also features hunters, a fish-tailed animal and other weird creatures. What is also remarkable, is that the stone has 4,000-year-old prehistoric cup marks on it. So this was re-using an already important stone.

The front has very fine details, some of which you may find below.

|

|

|

Meigle 2 measures over 2.5m and is a Class III stone as there are no symbols on it. Instead it is full of weird creatures, hunters, and other figures fuelling speculation the Arthurian legend is on this slab.

Meigle 2 measures over 2.5m and is a Class III stone as there are no symbols on it. Instead it is full of weird creatures, hunters, and other figures fuelling speculation the Arthurian legend is on this slab.

Most of it though, is biblical in origin.

As you can see, the front of the slab is very rich with the bosses in the cross very prominent. The panels siding the large rectangular display three individuals on the left,with the top one seemingly lifting the one underneath.

The right panel features three beasts with long bodies and large heads, with the top one seemingly having its head stuck.

The right panel features three beasts with long bodies and large heads, with the top one seemingly having its head stuck.

The reverse is equally fascinating. The top shows a bearder rider (probably the patron of the stone) carrying a spear and a sword. Next to him is a wee angel (his soul?) and two hunting dogs. Underneath are three riders abreast followed by a single rider.

|

|

|

The middle picture represents Daniel in the lion's den.

The third is a centaur with two axes and a branch of a tree.

At the bottom (see picture of complete slab) you can discern a man with a club and two beasts fighting.

I don't know how the numbering works, but it's definitely not according to size. This is Meigle 3: a "part of a slender grave-marker".

I don't know how the numbering works, but it's definitely not according to size. This is Meigle 3: a "part of a slender grave-marker".

One side is a cross, the reverse is a horse-rider, or a warrior. Personally, I think it's a small horse for a big man.

As you can see, the middle bit of Meigle 4 is missing.

As you can see, the middle bit of Meigle 4 is missing.

But still, plenty is left to gaze at. The cross is sided by fantastic beasts and under the right arm of the cross, parts are visbile of a man seemingly jumped upon by an animal.

The reverse has a horse-rider, knotwork and more animals.

And it also displays symbols. This time they are not on top of the slab, but underneath the horse-rider.  To the right you can clearly see the Pictish beast/elephant above the crescent and V-rod. So this particular stone could have been dedicated to or ordered by: Edern, son of Brude.

To the right you can clearly see the Pictish beast/elephant above the crescent and V-rod. So this particular stone could have been dedicated to or ordered by: Edern, son of Brude.

Meigle 5 has a beautifully carved cross on one side and a (decapitated) horse-ride on the reverse. While I usually prefer the reverse, this time, the front and side are more fascinating.

Meigle 5 has a beautifully carved cross on one side and a (decapitated) horse-ride on the reverse. While I usually prefer the reverse, this time, the front and side are more fascinating.  The top left features a beast biting its own tail, the bottom right displays a bird eating another birdlike creature and the botton left is - as far as I'm concerned - a cat. The very bottom is like an extension of the cross shaft and ends in snake-headed creatures.

The top left features a beast biting its own tail, the bottom right displays a bird eating another birdlike creature and the botton left is - as far as I'm concerned - a cat. The very bottom is like an extension of the cross shaft and ends in snake-headed creatures.

But it's the side that really got to me this time, as this is where the Pictish symbols are carved. Meigle 5 displays a mirror case (quite rare like this) above the Pictish beast/elephant.

You can already see that the top of Meigle 6 is missing as the cross itself is absent. Therefore, it's obvious that the reverse also misses something. At the very least, the head of the horse-rider - with shield.

You can already see that the top of Meigle 6 is missing as the cross itself is absent. Therefore, it's obvious that the reverse also misses something. At the very least, the head of the horse-rider - with shield.

Underneath are two symbols: double disc and crescent. According to Cummins, this could be: Cinaed/Kenneth, son of Ferat.

I will not list every numbered fragment in the museum, but please find a selection of what you may find at Meigle.

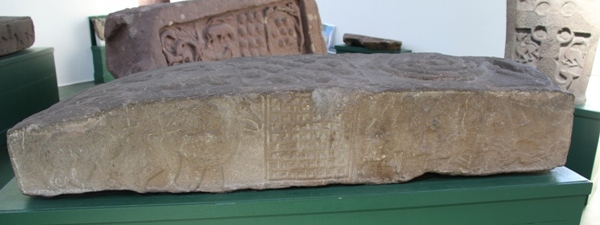

Meigle 11 is a "massive grave-cover".

Meigle 11 is a "massive grave-cover".

Left you can see one side; to the right a detail of the panel you can find in its entirety below.

Meigle 12 (see above) is another gigantic grave-cover. This time it features bulls on its side.

Meigle 12 (see above) is another gigantic grave-cover. This time it features bulls on its side.

The top is covered in lozenges (see picture on the right).

The reverse side of the cover is badly eroded.

Below Meigle 22, described as an "architectural fragment - part of a frieze". The impish devil in the middle surely has its feet caught in something.

This looks more Viking than Pictish, but it's still categorised as Pictish. This is Meigle 25, a late-tenth-century 'hogback', which is also a grave-cover. It is covered in 'roof-tiles'.

This looks more Viking than Pictish, but it's still categorised as Pictish. This is Meigle 25, a late-tenth-century 'hogback', which is also a grave-cover. It is covered in 'roof-tiles'.

The top of the cover is a snake. Both its head and the line below show knotwork, which makes it still Pictish.

Meet Meigle 26, another grave-cover. It is magnificently carved on all but one side.

This is the top.

This is one side. Please, do observe the naked men looking at naked behinds and holding each other's feet. The wild beasts on either side are naturally of secondary importance.

This is the other side. A grid in the middle, hunters on the right and animals on the left.

A big beast chasing a seemingly frightened man. The final panel of Meigle 26.

A big beast chasing a seemingly frightened man. The final panel of Meigle 26.

So, all this and more at Meigle. Definitely worth the visit. Very friendly staff. Once around the block and you'll find it. Maybe it's a bit more visible since we were there. Don't miss this. It would be an utter shame.

Nigg Stone

Our final destination of day trip exploring the Highland Pictish Trail: the Nigg Stone.

Our final destination of day trip exploring the Highland Pictish Trail: the Nigg Stone.  As you can see, the stone has a section missing, and it has a rather ugly surgical metal pin holding it erect.

As you can see, the stone has a section missing, and it has a rather ugly surgical metal pin holding it erect.

For its protection, it has therefore been moved inside Nigg Church, a lovely wee church with a Cholera Stone outside (Cholera ceased to exist in that parish by putting a stone on the disease). Clever right?

The cross side is rather beautiful indeed. Just admire some of the details on the following pictures.

The cross side is rather beautiful indeed. Just admire some of the details on the following pictures.

|

|

|

The cross side is obviously the most important one to observe, at least according to those individuals putting it into position.

The cross side is obviously the most important one to observe, at least according to those individuals putting it into position.  Because there is no way you can take a picture of the symbol side in one go. Isn't that just typical?

Because there is no way you can take a picture of the symbol side in one go. Isn't that just typical?

Maybe it's because half of the symbols are missing. You can still see the eagle (Dunodnat), but most of the Pictish beast (Edern) is missing.

Still, after a full day in the trail of Pictish stuff on the Tarbat peninsula, the Nigg Stone is definitely worth the visit.

Portmahomack

Rosemarkie

The Rosemarkie Pictish stone currently "only" measures 2.2m, but as you can already detect from the picture to the left, the top is missing. The original - complete - stone may have stood to at least 2.75m. So indeed, rather impressive.

The Rosemarkie Pictish stone currently "only" measures 2.2m, but as you can already detect from the picture to the left, the top is missing. The original - complete - stone may have stood to at least 2.75m. So indeed, rather impressive.

It was found buried "within" Rosemarkie church and after some time braving the elements outside, it was moved inside Groam House Museum (in Rosemarkie), where you can admire it at leisure. As you can spot on some pictures, some tourist really was at ease, hence this stone-with-legs version of this fine Pictish stone.

There are three symbols on the symbol side.

The top of the stone is damaged, but the crescent and V-rod is still very clear.

Underneath is a double disc and Z-rod.

And below again a - remarkably different

- crescent and V-rod.

So according to Cummins, this is Brude, son of Drust, son of Brude.

The other side has two panels of knot work, the top one containing a small squared Christian cross.

The other side has two panels of knot work, the top one containing a small squared Christian cross.

A lot of the interlacing has faded, but it is still visible enough to demonstrate the craftsmanship of its creator. The side panels too are covered with lace work.

That is not all that is to be seen in Groam House Museum. Fragments of or smaller Pictish stones can also be found lining the walls of this small museum. The one where a beast is about to devour a man is particularly graphic. Biblical pictures, right.

|

|

|

|

|

All this at Groam House Museum. More info here.

St Andrews Sarcophagus

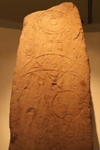

This is the St Andrew's Sarcophagus, a magnificently sculptured piece of art. It is considered the "finest example of Pictish sculpture in Scotland". As you can see, its original shape must have been four panels that slotted into corner-posts.

This is the St Andrew's Sarcophagus, a magnificently sculptured piece of art. It is considered the "finest example of Pictish sculpture in Scotland". As you can see, its original shape must have been four panels that slotted into corner-posts.

The front slab is the one that is best preserved. It is full of biblical scenes.

The front slab is the one that is best preserved. It is full of biblical scenes.

The first picture below shows David riding a horse. On his arm he has a falcon and in his other hand he holds a sword, ready to strike at the lion in front of him.

|

|

|

The second picture is David fighting the lion, excuse me, "rending the jaws of the lion". This figure is considerably larger than the rest on the panel.

The third figure is David again, as a good shepherd.

These are the "panels" siding the main one.

And these are the panels 'slotted' in-between. As you can discern, one is considerable more intact than the other.

And now comes another hotly debated topic.

Who lay in this elaborately carved sarcophagus? The board in the Cathedral reads that it was Oengus/Onuist, son of Fergus. This Pictish king certainly had a link with St Andrews, or rather Cennrígmonaid, as it was called back then. The only "issue" with this, is that Oengus died in 761, and although the Sarcophagus is difficult to date, the lack of any symbols makes it likely that it was a later work rather than an early Pictish stone. So is Oengus still the most likely candidate?

Cummins reasons that Constantine, son of Aed, who ruled between 900 and 943, is a more likely candidate. He abdicated to retire to St Andrews, where he became a monk. He was also the last recorded king of Picts. After him, the reign of the Scots started.

So who knows who the Sarcophagus was for? Maybe we will never know.

So who knows who the Sarcophagus was for? Maybe we will never know.

In any case, definitely worth to go and see.

In the same room, there is another fine Pictish slab.

And while you're there at St Andrews Cathedral, you can admire the many other fine artefacts.

St Orland's Stone

Now this is a stone that is quite a challenge and I met several museum guards who admitted they had not seen this one because of its position. I am usually all for keeping a stone where it is found, but I would be willing to make an exception here. To get to this magnificent specimen, you have to wade through a field of nettles, slightly tresspass on a farmer's field and then climb through/over fencing. It would be a lot simpler if the farmer kept the path clear and showed the way, but there you go. In any case, the day I took these photographs, it was hot (aye, that can happen in Scotland) and I wore short pants and regular shoes which added considerably to the challenge. Something Prof. MacGregor also faced.

Now this is a stone that is quite a challenge and I met several museum guards who admitted they had not seen this one because of its position. I am usually all for keeping a stone where it is found, but I would be willing to make an exception here. To get to this magnificent specimen, you have to wade through a field of nettles, slightly tresspass on a farmer's field and then climb through/over fencing. It would be a lot simpler if the farmer kept the path clear and showed the way, but there you go. In any case, the day I took these photographs, it was hot (aye, that can happen in Scotland) and I wore short pants and regular shoes which added considerably to the challenge. Something Prof. MacGregor also faced.

St Orland's Stone dates from the eighth or possibly the early ninth century and is also referred to as the Cossans Stone (because of where it is found). Its symbols are a crescent and V-rod above a double disc and Z-rod (so Brude, son of Drust).

St Orland's Stone dates from the eighth or possibly the early ninth century and is also referred to as the Cossans Stone (because of where it is found). Its symbols are a crescent and V-rod above a double disc and Z-rod (so Brude, son of Drust).

But why did I really, really want to see this particular stone? Because of the unique detail on the right: it is the only known picture of a Pictish boat.

St Vigeans Museum including the Drosten Stone

St Vigeans Museum is a small house full, really full of Pictish stones. I didn't count them but there are over 30 Pictish stones in there. When interested in the Picts, this one you cannot miss. But please, do read the warning at the end of this piece.

St Vigeans Museum is a small house full, really full of Pictish stones. I didn't count them but there are over 30 Pictish stones in there. When interested in the Picts, this one you cannot miss. But please, do read the warning at the end of this piece.

The museum uses this lovely stone (St Vigeans 21) to the left as its "symbol" (read: you can stamp a picture of this deer on a piece of paper), even though the stone is found fairly to the back of the small house. But I guess it was easier to use and reprint this animal than its prize stone which does take a prime position in the room.

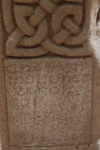

This is the Drosten Stone (St Vigeans 1). With its 1.75m and only 0.55m wide, it isn't the most sizeable stone. Its carving on the other hand, is quite impressive and detailed, as you will see from the various pictures below. But what makes itreally special is the fact that - unlike all other stones in the museum which merely obtained a number - this stone has a name, a proper name. And it is this stone that Cummins used to start to decipher the Pictish symbols and link them to a name.

This is the Drosten Stone (St Vigeans 1). With its 1.75m and only 0.55m wide, it isn't the most sizeable stone. Its carving on the other hand, is quite impressive and detailed, as you will see from the various pictures below. But what makes itreally special is the fact that - unlike all other stones in the museum which merely obtained a number - this stone has a name, a proper name. And it is this stone that Cummins used to start to decipher the Pictish symbols and link them to a name.

The side of the stone bears the following inscription:

The side of the stone bears the following inscription:

Drosten

ipeuroret / ettfor / cus

Drosten or Drust may be the Pictish form of "Tristan" (meaning thunder).

Cummins reasons "ipe" may stand for "son of". "Uoret" equals a variety of names (here we go): Wrad, Urad, Uúrad, or Ferat, Ferach, Ferech, Feradach. Combined with the symbols on the stone, this means that the double disc and Z-rod above a crescent could mean: Drust, son of Ferat. The comb and mirror are (again) an in memory of. A Drust, son of Ferat was one of the leaders fighting against Cinaed son of Alpin (more popularly know as Kenneth mac Alpin).

|

|

|

Underneath the symbols is a "pastoral scene". A hunter is chasing a boar; the second picture shows a bird of prey catching a salmon, a bear; the third is a detail of a doe suckling a fawn.

The "front" side - so the one with the cross - features deformed monsters, some with interwoven tails and legs. But I particularly loved the figure in the top left corner. Instead of an angel, the Drosten Stone displays a wee impish devil.

The "front" side - so the one with the cross - features deformed monsters, some with interwoven tails and legs. But I particularly loved the figure in the top left corner. Instead of an angel, the Drosten Stone displays a wee impish devil.

There is another cross-slab which is also eye-catching: St Vigeans 7. The top did not survive and it is thought the slab must have been over 2m high and 1m wide. As you can see from the pictures left and right, the front is in better shape than the back. Both front and back have a cross. It is thought to be one of St Vigeans' earliest cross-slabs.

There is another cross-slab which is also eye-catching: St Vigeans 7. The top did not survive and it is thought the slab must have been over 2m high and 1m wide. As you can see from the pictures left and right, the front is in better shape than the back. Both front and back have a cross. It is thought to be one of St Vigeans' earliest cross-slabs.

The cross on the front of St Vigeans 7 contains some beautiful and special elements, such as the three heads you find in detail to the right.

The cross on the front of St Vigeans 7 contains some beautiful and special elements, such as the three heads you find in detail to the right.

But it's especially the panels siding the cross that feature quite a number of Christian designs, or moral lessons.

What to make of this?

If you have faith, food will be plentiful (though a thousand-odd years may be less kind to how you end up depicted on a cross-slab), while if you continue your heretic and pagan belief, you will be forced to drink a bull's blood to survive.

|

|

|

I did not add pictures here of every cross-slab, grave-marker, cross, 'house shrine', etc. Just a small selection of what can be gazed at in St Vigeans.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

St Vigeans 11 has another "special" feature. If you look carefully, you may discern cuts made across the body of one of the figures. It's thought that this was designed to swear an oath. You'd swear to stick to your oath by cutting on the heart of the cleric depicted.

St Vigeans 11 has another "special" feature. If you look carefully, you may discern cuts made across the body of one of the figures. It's thought that this was designed to swear an oath. You'd swear to stick to your oath by cutting on the heart of the cleric depicted.

And that's how you get away with vandalism.

One final note: St Vigeans is opened only after you make an appointment. You might get lucky - like some tourists who happened to visit when we were there - but to avoid disappointment, phone, make a reservation and a very friendly guide from Arbroath Abbey will come over and open St Vigeans Museum. It is worth visiting both the Abbey and the museum in one day. But do phone ahead.

Shandwick Stone

Also part of our day trip following part of the Highland Pictish trail, this fine stone, also dubbed Clach' Charaidh (stone of the graves) is situated on its place of origin, which isn't all that obvious these days.

Also part of our day trip following part of the Highland Pictish trail, this fine stone, also dubbed Clach' Charaidh (stone of the graves) is situated on its place of origin, which isn't all that obvious these days.

As you may notice, the years of exposure have done some damage, so to protect it from further erosion, the stone is put in a glass shelter. If you phone, though, you can get inside the shelter to admire it up close and get decent pictures. Only one serious bummer. They should have made the shelter a wee bit bigger as you cannot take a picture of the Shandwick Stone in its entirety.

The cross side is quite lavish, with big bosses, beasts ands spirals.

The cross side is quite lavish, with big bosses, beasts ands spirals.

I am, however, always a bigger fan of the symbol side, especially since this one holds one of the Picts' "most endearing creations".

Above an elaborate hunting scene, there are two symbols. On top the double disc (Kenneth) and then the symbol rather frequently occurring on the Tarbat peninsula: the Pictish beast (Edern).

Above an elaborate hunting scene, there are two symbols. On top the double disc (Kenneth) and then the symbol rather frequently occurring on the Tarbat peninsula: the Pictish beast (Edern).

Certainly worth the visit, especially when you phone and get to meet one of the people in charge of preserving the stone.

Struan Church Pictish stone

This Class I stone is found inside Struan Church, Struan, a small place north of Pitlochry.

This Class I stone is found inside Struan Church, Struan, a small place north of Pitlochry.

It features one symbol only: a double disc and Z-rod.

So this stone could commemorate Drust.

Sueno's Stone

This specimen is the largest Pictish stone, measuring 7m tall. It is probably situated where it was originally erected, overlooking the marshy floodplains of the rivers Mosse and Findhorn, to the west of Elgin.

This specimen is the largest Pictish stone, measuring 7m tall. It is probably situated where it was originally erected, overlooking the marshy floodplains of the rivers Mosse and Findhorn, to the west of Elgin.

It is elaboratically carved on all sides, with a cross on one side and a battle scene on the other.

As you can see on the pictures, the stone is protected in a glass cage, making it impossible to take decent pictures.

Apart from that, the stone is a must-see. Gigantic, telling a story, or - as one historian put it - 'Sueno's Stone is on an unusually ambitious scale':  cavalry, foot soldiers and beheading of the defeated (see rather poor picture on the left). It is, however, not clear what battle it depicts. The problem of the Picts, right.

cavalry, foot soldiers and beheading of the defeated (see rather poor picture on the left). It is, however, not clear what battle it depicts. The problem of the Picts, right.

An explanatory board at the site offers three possibilities:

* The battle depicts the Scots defeating the Picts, like Cinaed son of Ailpin (aka Kenneth mac Alpin) making his mark over the Picts. Personally I think: noop.

* It could be a battle between Picts and Scots on one side and Norsemen on the other.

They had their fair share of those, with the Norsemen usually on the winning side.

* A third possibility is a battle fought at Forris

in 996 and in this struggle the Scottish king Dubh was killed by the men of Moray (Picts). On the stone there is a specially framed head, so maybe it's Dubh's. Who knows?

On the other side there is the remarkable 'inauguration scene', which is similar to the common seal of the Abbey of Scone. So who was the now completely wiped-out king in the middle?

Lots of questions and more pictures below, all taken through the glass window. So there you go.

|

|

|

Tarbat Discovery Centre - Portmahomack

This tiny museum is a gem and a great start to begin your Pictish day exploring the Tarbat peninsula. Yep, this museum is part of the Highland Pictish Trail, a route you can take of all things Pictish between Inverness and Dunrobin Castle. We didn't do all of that in one day, but when touring, it's quite a nice day to start in Portmahomack and descend the peninsula on the B9165, passing the Hilton of Cadboll (replica), Shandwick, and finally, Nigg Pictish stones.

This tiny museum is a gem and a great start to begin your Pictish day exploring the Tarbat peninsula. Yep, this museum is part of the Highland Pictish Trail, a route you can take of all things Pictish between Inverness and Dunrobin Castle. We didn't do all of that in one day, but when touring, it's quite a nice day to start in Portmahomack and descend the peninsula on the B9165, passing the Hilton of Cadboll (replica), Shandwick, and finally, Nigg Pictish stones.

But first things first: Tarbat Discovery Centre in Portmahomack. The village itself was an important Pictish centre with monastery. This monastery was destroyed between 780 and 830 and was unearthed again only recently. FA-SCI-NA-TING!

But first things first: Tarbat Discovery Centre in Portmahomack. The village itself was an important Pictish centre with monastery. This monastery was destroyed between 780 and 830 and was unearthed again only recently. FA-SCI-NA-TING!

Inside the museum you can find documentation about the history of the place and there's a video running as well. Of course, there arre also

Inside the museum you can find documentation about the history of the place and there's a video running as well. Of course, there arre also  fragments of Pictish stones.

fragments of Pictish stones.

One of them is the Dragon Stone which is placed behind glass (really) and takes centre space. The stone actually has two names: Dragon Stone and (because of the figures on the other side) the Apostle Stone.

Another beauty is the one below. Pictish art: lovely.

|

|

|

Close to the museum, at the car park, you can admire this beautiful statue: the Pictish Queen. This has everything to do with a Pictish stone further down the road: the Hilton of Cadboll. More info over there.

Close to the museum, at the car park, you can admire this beautiful statue: the Pictish Queen. This has everything to do with a Pictish stone further down the road: the Hilton of Cadboll. More info over there.

Home

Home